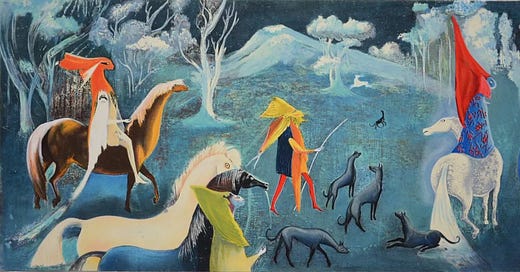

Figuras fantásticas a caballo (1952) by Leonora Carrington

We moved in with my mom right before Hurricane Helene arrived. We had a week of rain and then more rain and then, as the hurricane came closer, a tornado warning that sent us into my mom’s very interesting basement, where most of her roommates live.

Water started coming in under the basement door…